Introdução por Jeff Tweedy, trecho de “Vamos Nessa (Para Podermos Voltar) – Memórias de Discos e Discórdias com o Wilco, etc…”, biografia do líder do Wilco que ganhouu edição brasileira via Editora Terreno Estranho, com tradução de Paulo Alves. A biografia já está disponível em livrarias e no site da editora:

“Esse talvez seja o melhor texto de rock and roll já escrito. Porque não é só sobre música (…). Você tem que ler o ensaio inteiro. Não, sério, vai ler agora. Vou esperar. Se você for como eu, talvez te faça chorar. (…) Me faz chorar toda vez que o leio. Já o li em voz alta para os meus filhos, e nunca consegui chegar até o final sem engasgar. Significa isso tudo para mim. (…) Sempre que retorno a esse texto – e eu retorno a ele da maneira como algumas pessoas se referem a suas passagens bíblicas favoritas -, a sensação é libertadora”.

por Lester Bangs

Texto publicado originalmente em três semanas na NME, dias 10, 17 e 24/12/1977

Part One: Six days on the road with the foremost garage band in the land

THE EMPIRE may be terminally stagnant, but every time I come to England it feels like massive changes are underway.

First time was 1972 for Slade, who had the punters hooting, but your music scene in general was in such miserable shape that most of the hits on the radio were resurrected oldies. Second time was for David Essex (haw haw haw) and Mott (sigh) almost exactly two years ago: I didn’t even bother listening to the radio, and though I had a good time the closest thing to a musical highlight of my trip was attending an Edgar Froese (entropy incarnate) press party. I never gave much of a damn about pub rock, which was about the only thing you guys had going at the time, and I had just about written you off for dead when punk rock came along.

So here I am back again through the corporate graces of CBS International to see The Clash, to hear new wave hands on the radio (a treat for American ears) and find the empire jumping again at last.

About time, too. I don’t know about you, but as far as I was concerned things started going downhill for rock around 1968; I’d date it from the ascendance of Cream, who were the first fake superstar band, the first sign of strain in what had crested in 1967. Ever since then things have just gotten worse, through Grand Funk and James Taylor and wonderful years like 1974, when the only thing interesting going on was Roxy Music, finally culminating last year in the ascendance of things like disco and jazz-rock, which are dead enough to suggest the end of popular music as anything more than room spray.

I was thinking of giving up writing about music altogether last year when all of a sudden I started getting phone calls from all these slick magazine journalists who wanted to know about this new phenomenon called “punk rock.” I was a little bit confused at first, because as far as I was concerned punk rock was something which had first raised its grimy snout around 1966 in groups like The Seeds and Count Five, and was dead and buried after The Stooges broke up and The Dictators’ first LP bombed.

I mean, it’s easy to forget that just a little over a year ago there was only one thing: the first Ramones album. But who could have predicted that that record would have such an impact—all it took was that and the ferocious edge of The Sex Pistols’ “Anarchy In The UK,” and suddenly it was as if someone had unleashed the floodgates as ten million little groups all over the world came storming in, mashing up the residents with their guitars and yammering discontented non sequiturs about how bored and fed up they were with everything.

I was too, and so were you—that’s why we went out and bought all those shitty singles last spring and summer by the likes of The Users and Cortinas and Slaughter and the Dogs, because better Slaughter and the Dogs at what price wretchedness than one more mewly-mouthed simperwhimper from Linda Ronstadt. Buying records became fun again, and one reason it did was that all these groups embodied the who-gives-damn-damn-let’s-slam-it-it-at-’em spirit of great rock ’n’ roll. Unfortunately many of these wonderful slices of vinyl didn’t possess any of the other components of same, with the result that (for me, round about Live at the Roxy) many people simply got FED UP. Meaning that it’s just too goddam easy to slap on a dog collar and black leather jacket and start puking all over the room about how you’re gonna sniff some glue and stab some backs.

Punk had reaped the very attitudes it copped (BOREDOM and INDIFFERENCE), and we were all waiting for a group to come along who at least went through the motions of GIVING A DAMN about SOMETHING. Ergo, The Clash. YOU SEE, dear reader, so much of what’s (doled) out as punk merely amounts to saying I suck, you suck, the world sucks, and who gives a damn—which is, er, ah, somehow insufficient.

Don’t ask me why, I’m just an observer, really, But any observer could tell that, to put it in terms of Us vs. Them, saying the above is exactly what They want you to do, because it amounts to capitulation. It is unutterably boring and disheartening to try to find some fun or meaning while shoveling through all the shit we’ve been handed the last few years, but merely puking on yourself is not gonna change anything. (I know, ’cause I tried it.) I guess what it all boils down to is:

(a) You can’t like people who don’t like themselves; and

(b) You gotta like somebody who stands up for what they believe in, as long as what they believe in is

(c) Righteous.

A precious and elusive quantity, this righteousness. Needless to say, most punk rock is not exactly OD-ing on it. In fact, most punk rockers probably think it’s the purview of hippies, unless you happen to be black and Rastafarian, in which case righteousness shall cover the land, presumably when punks have attained No Future. It’s kinda hard to put into mere mortal words, but I guess I should say that being righteous means you’re more or less on the side of the angels, waging Armageddon for the ultimate victory of the forces of Good over the Kingdoms of Death (see how perilously we skirt hippiedom here?), working to enlighten others as to their own possibilities rather than merely sprawling in the muck yodelling about what a drag everything is.

The righteous minstrel may be rife with lamentations and criticisms of the existing order, but even if he doesn’t have a coherent program for social change he is informed of hope. The MC5 were righteous where The Stooges were not. The third and fourth Velvet Underground albums were righteous, the first and second weren’t. (Needless to say, Lou Reed is not righteous.) Patti Smith has been righteous. The Stones have flirted with righteousness (e.g.,“Salt Of The Earth”), but when they were good The Beatles were all-righteous. The Sex Pistols are not righteous, but, perhaps more than any other new wave band, The Clash are.

The reason they are is that beneath their wired harsh soundscape lurks a persistent humanism. It’s hard to put your finger on in the actual lyrics, which are mostly pretty despairing, but it’s in the kind of thing that could make somebody like Mark P. write that their debut album was his life. To appreciate it in The Clash’s music you might have to be the sort of person who could see Joe Strummer crying out for a riot of his own as someone making a positive statement. You perceive that as much as this music seethes with rage and pain, it also champs at the bit of the present system of things, lunging after some glimpse of a new and better world.

I know it’s easy to be cynical about all this; in fact, one of the most uncool things you can do these days is to be committed about anything. The Clash are so committed they’re downright militant. Because of that, they speak to dole-queue British youth today of their immediate concerns with an authority that nobody else has quite mustered. Because they do, I doubt if they will make much sense to most American listeners.

But more about that later. Right now, while we’re on the subject of politics. I would like to make a couple of things perfectly clear:

1. I do not know shit about the English class system.

2. I don’t [sic] not care shit about the English class system.

I’ve heard about it, understand. I’ve heard it has something to do with why Rod Stewart now makes music for housewives, and why Townshend is so screwed up. I guess it also has something to do with another NME writer sneering to me “Joe Strummer had a fucking middle class education, man!” I surmise further that this is supposed to indicate that he isn’t worth a shit, and that his songs are all fake street-graffiti. Which is fine by me: Joe Strummer is a fake. That only puts him in there with Dylan and Jagger and Townshend and most of the other great rock song writers, because almost all of them in one way or another were fakes. Townshend had a middle-class education. Lou Reed went to Syracuse University before matriculating to the sidewalks of New York. Dylan faked his whole career; the only difference was that he used to be good at it and now he sucks.

The point is that, like Richard Hell says, rock ’n’ roll is an arena in which you recreate yourself, and all this blathering about authenticity is just a bunch of crap. The Clash are authentic because their music carries such brutal conviction, not because they’re Noble Savages.

HERE’S a note to CBS International: you can relax because I liked The Clash as people better than any other band I have ever met with the possible exception of Talking Heads, and their music it goes without saying is great (I mean you think so, don’t you? Good, then release their album in the U.S. So what if it gets zero radio play; Clive knew how to subsidize the arts.) Here’s a superlative for ads: “Best band in the UK!”—Lester Bangs. Here’s another one: “Thanks for the wonderful vacation!”—Lester Bangs. (You know I love you, Ellie.) Okay, now that all that’s out of the way, here we go . . .

I WAS sitting in the British Airways terminal in New York City on the eve of my departure, reading The War Against The Jews 1933-1945 when I looked up just in time to see a crippled woman in a wheelchair a few feet away from me. My eyes snapped back down to my book in that shameful nervous reflex we know so well, but a moment later she had wheeled over to a couple of feet from where I was sitting, and when I could fight off the awareness of my embarrassment at her presence no longer I looked up again and we said hello to each other.

She was a very small person about 30 years old with a pretty face, blonde hair and blazing blue eyes. She said that she had been on vacation in the States for three months and was now, ever so reluctantly, returning to England. “I like the people in America so much better,” she said. “Christ, it’s so nice to be someplace where people recognize that you exist. In England, if you’re handicapped no one will look at or speak to you except old people. And they just pat you on the head.”

IT IS four days later, and I’ve driven from London to Derby with Ellie Smith from CBS and Clash manager Bernard Rhodes for the first of my projected three nights and two days with the hand. I am not in the best of shape since I’ve still got jet-lag, have been averaging two to three hours sleep a night

I got here, and the previous night was stranded in Aylesbury by the Stiff’s Greatest Hits tour, hitching a ride back to London with a roadie in the course of which we were stopped by provincial police in search of dope and forced to empty all our pockets, something which had not happened to me since the hippie heydaze of 1967. This morning when I went by Mick Farren’s flat to pick up my bags he had told me “You look like ‘Night Of The Living Dead.’”

Nevertheless, I make sure after checking into the Derby Post House to hit the first night’s gig, whatever my condition, in my most thoughtful camouflage. You see, the kind of reports we get over in the States about your punk rock scene had led me to expect seething audiences of rabid little miscreants out for blood at all costs, and naturally I figured the chances of getting a great story were better if I happened to get cannibalized. So I took off my black leather jacket and dressed as straight as I possibly could, the coup de grace (I thought) being a blue promotional sweater that said “Capitol Records” on the chest, by which I fantasized picking up some residual EMI-hostility from battle-feral Pistols fans. I should mention that I also decided not to get a haircut which I desperately needed before leaving the States, on the not-so-off chance of being mistaken for a hippie.

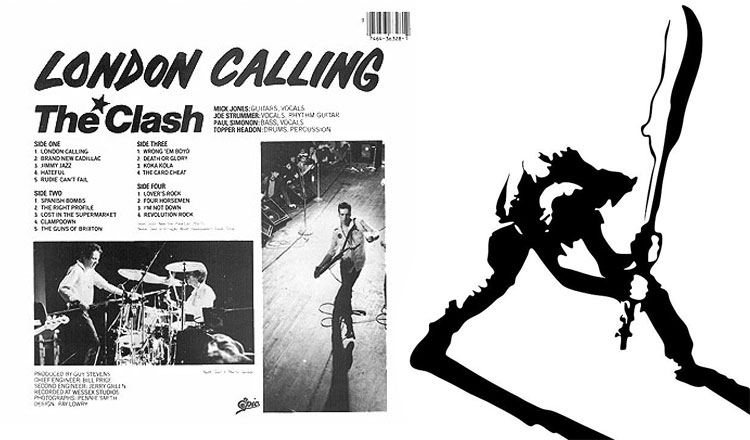

When I came out of my room and Ellie and photographer Pennie Smith saw me, they laughed. When I got to the gig I pushed my way down through the pogoing masses, right into the belly of the beast, and stood there through openers The Lous and Richard Hell and the Voidoids’ sets, waiting for the dog soldiers of anarch-apocalypse to slam my skull into my ankles under a new wave riptide. Need I mention that nothing of the kind transpired? Listen: if I were you I would take up arms and march on the media centers of Merrie Old, NME included, and trash them beyond recognition. Because what I experienced, this first night and all subsequent on this tour, was so far from what we Americans’ve read in the papers and seen on TV that it amounts to a mass defamation of character, if not cultural genocide.

Nobody gave a damn about my long hair, or could have cared less about some stupid sweater. Sure there was gob and beercups flung at the bands, and the mob was pushing sideways first right and then left, but I hate to disappoint anybody who hasn’t been there but this scene is neither Clockwork Orange nor Lord Of The Flies. When I got tired of the back-and-forth group shove I simply stuck my elbows out and a space formed around me. What I am saying is that I have been at outdoor rock festivals in the hippie era in America where the vibes and violence were ten times worse than at any of the gigs I saw on this Clash tour, and the bands said later that this Derby engagement was the worst they had seen. What I am saying is that contrary to almost all reports published everywhere, I found British punks everywhere I went to be basically if not manifestly gentle people. They are a bunch of nice boys and girls and don’t let anybody (them included) tell you different.

Yeah, they like to pogo. On the subject of this odd tribal rug-cut, of course the first thing I saw when I entered the hall was a couple of hundred little heads near the lip of the stage all bobbing up and down like anthropomorphized pistons in some Max Fleischer cartoon on the Industrial Revolution.

When I’d heard about pogoing before I thought it was the stupidest thing anybody’d ever told me about, but as soon as I saw it in living sproing it made perfect sense. I mean, it’s obviously no more stupid than the seconal idiot-dance popularized five years ago by Grand Funk audiences. In fact, it’s sheer logic (if not poetry) in motion: when you’re packed into a standing sweatshop with ten thousand other little bodies all mashed together, it stands to reason you can’t dance in the traditional manner (ie sideways sway). No, obviously if you wanna do the boogaloo to what the new breed say you gotta by dint of sheer population explosion shake your booty and your body in a vertical trajectory. Which won’t be strictly rigid anyway since because this necessarily involves losing your footing every two seconds the next step is falling earthward slightly sideways and becoming entangled with your neighbours, which is as good a way as any of making new friends if not copping a graze of tit.

There is, however, one other aspect of audience appreciation which ain’t nearly so cute: gobbing. For some reason this qualifies as news to everybody, so I’m gonna serve notice right here and now: LISTEN YA LITTLE PINHEADS, IT’S NAUSEATING AND MORONIC, AND I DON’T MEAN GOOD MORONIC, I MEAN JERKED OFF. THE BANDS ALL HATE IT (the ones I talked to, anyway) AND WOULD ALL PLAY BETTER AND BE MUCH HAPPIER IF YOU FIGURED OUT SOME MORE ORIGINAL WAY OF SHOWING YOUR APPRECIATION.

(After the second night I asked Mick Jones about it and he looked like he was going to puke. “But doesn’t it add to the general atmosphere of chaos and anarchy?” I wondered “No,” he said. “It’s fucking disgusting.”)

END OF moral lecture. The Clash were a bit of a disappointment the first night. They played well, everything was the right place, but the show seemed to lack energy somehow. A colleague who saw them a year ago had come back to the States telling me that they were the only group he’d ever seen on stage who were truly wired. It was this I was looking for and what I got in its place was mere professionalism, and hell, I could go let The Rolling Stones put me to sleep again if that was all I cared about. Back up in the dressing room I cracked “Duff gig, eh fellas?” and they laughed, but you could tell they didn’t think it was funny. Later I found out that Joe Strummer had an abcessed tooth which had turned into glandular fever, and since the rest of the band draw their energy off him they were all suffering. By rights he should have taken a week off and headed straight for the nearest hospital, but he refused to cancel any gigs, no mere gesture of integrity.

A process of escalating admiration for this band had begun for me which was to continue until it broached something like awe. See, because it’s easy to sing about your righteous politics, but as we all know actions speak louder than words, and The Clash are one of the very few examples I’ve seen where they would rather set an example by their personal conduct than talk about it all day.

Case in point. When we got back their hotel I had a couple of interesting lessons to learn. First thing was they went up to their rooms while Ellie, Pennie, a bunch of fans and me sat in the lobby. I began to make with the grouch squawks because if there’s one thing I have learned to detest over the years it’s sitting around some goddam hotel lobby like a soggy douchebag parasite waiting for some lousy high and mighty rock’n’roll band to maybe deign to put in an imperial appearance.

But then a few minutes later The Clash came down and joined us and I realized that unlike most of the bands I’d ever met they weren’t stuck up, weren’t on a star trip, were in fact genuinely interested in meeting and getting acquainted with their fans on a one-to-one, non-condescending level.

Mick Jones was especially sociable, so I moved in on him and commenced my second mis-informed balls-up of the evening. A day or two earlier I’d asked Mick Farren what sort of questions he thought might he appropriate for The Clash, and he’d said, “Oh, you might do what you did with Richard Hell and ask ’em just exactly what their political program is, what they intend to do once they get past all the bullshit rhetoric. Mind you, it’s liable to get you thrown off the tour.” So, vainglorious as ever, I zeroed in on Mick and started drunkenly needling him with what I thought were devastating barbs. He just laughed at me and parried every one with a joke, while the fans chortled at the spectacle of this oafish American with all his dumbass sallies. Finally he looked me right in the eye and said, “Hey Lester: why are you asking me all these fucking questions?” In a flash I realized that he was right. Here was I, a grown man, travelling all the way across the Atlantic ocean and motoring up into the provinces of England, just to ask a goddam rock ’n’ roll band for the meaning of life! Some people never learn. I certainly didn’t, because I immediately started in on him with my standard cultural-genocide rap: “Blah blah blah depersonalization blab blab blab solipsism blah blab yip yap etc . . .”

“What in the fuck are you talking about?”

“Blah blab no one wants to have any emotions any more blab blip human heart an endangered species blah blare cultural fascism blab blurb etc. etc. etc. . . .”

“Well,” says Mick, “don’t look at me. If it bothers you so much why don’t you do something about it?”

“Yeah,” says one of the fans, a young black punk girl sweet as could be, “you’re depressing us all!” Seventeen punk fan spike heads nod in agreement. Mick just keeps laughing at me.

SO, HAVING bummed out almost the entire population of one room, I took my show into another: the bar, where I sat down at a table with Ellie and Paul Simonon and started in on them. Paul gets up and walks out. Ellie says, “Lester, you look a little tired. Are you sure you want another lager . . . ?”

Later I am out in the lobby with the rest of them again, in a state not far from walking coma, when Mick gestured at a teenage fan sitting there and said “Lester, my room is full tonight; can Adrian stay with you?” I finally freaked. Here I was, stuck in the middle of a dying nation with all these funny looking children who didn’t even realize the world was coming to an end, and now on top of everything else they expected me to turn my room into a hippie crash pad! I surmised through all my confusion that some monstrous joke was being played on me, so I got testy about it, Mick repeated the request and finally I said that Adrian could maybe stay but he would have to go to the house phone, call my hotel and see if there was room. So the poor humiliated kid did just that while an embarrassed if not downright creepy silence fell over the room and Mick stared at me in shock, as if he had never seen this particular species of so-called human before.

Poor Adrian came back saying there was indeed room, so I grudgingly assented, and back to the hotel we went. The next morning, when I was in a more sober if still jet-lagged frame of mind, he showed me a copy of his Clash fanzine 48 Thrills which I bought for 20p, and in the course of breakfast conversation learned that The Clash make a regular practice of inviting their fans back from the gigs with them, and then go so far as to let them sleep on the floors of their rooms. Now, dear reader, I don’t know how much time you may have actually spent around bigtime rock ’n’ roll bands—you may not think so, but the less the luckier you are in most cases—but let me assure you that the way The Clash treat their fans falls so far outside the normal run of these things as to be outright revolutionary. I’m going to say it and I’m going to say it slow: most rockstars are goddamn pigs who have the usual burly corps of hired thugs to keep the fans away from them at all costs, excepting the usual select contingent of lucky (?) nubiles who they’ll maybe deign to allow up to their rooms for the privilege of sucking on their coveted wangers, after which often as not they get pitched out into the streets to find their way home without even cabfare. The whole thing is sick to the marrow, and I simply could not believe that any hand, especially one as musically brutal as The Clash, could depart so far from this fetid norm.

I mentioned it to Mick in the van that day en route to Cardiff, also by way of making some kind of amends for my own behaviour: “Listen, man, I’ve just got to say that I really respect you . . . I mean, I had no idea that any group could be as good to its fans as this . . .”

He just laughed. “Oh, so is that gonna be the hook for your story, then?”

AND THAT for me is the essence of The Clash’s greatness, over and beyond their music, why I fell in love with them, why it wasn’t necessary to do any boring interviews with them about politics or the class system or any of that: because here at last is a band which not only preaches something good but practices it as well, that instead of talking about changes in social behaviour puts the model of a truly egalitarian society into practice in their own conduct.

The fact that Mick would make a joke out of it only shows how far they’re going towards the realization of all the hopes we ever had about rock ’n’ roll as utopian dream—because if rock ’n’ roll is truly the democratic artform, then the democracy has got to begin at home, that is the everlasting and totally disgusting walls between artists and audience must come down, elitism must perish, the “stars” have got to be humanized, demythologized, and the audience has got to be treated with more respect. Otherwise it’s all a shuck, a ripoff, and the music is as dead as the Stones’ and Led Zep’s has become.

It’s no news by now that the reason most of rock’s establishment have dried up creatively is that they’ve cut themselves off from the real world of everyday experience as exemplified by their fans. The ultimate question is how long a group like The Clash can continue to practice total egalitarianism in the face of mushrooming popularity. Must the walls go up inevitably, eventually, and if so when? Groups like The Grateful Dead have practiced this free-access principle at least in the past, but the Dead never had glamour which, whether they like it or not (and I’d bet money they do) The Clash are saddled with—I mean, not for nothing does Mick Jones resemble a young and already slightly dissipated Keith Richard— besides which the Dead aren’t really a rock ’n’ roll band and The Clash are nothing else but. And just like Mick said to me the first night, don’t ask me why I obsessively look to rock ’n’ roll bands for some kind of model for a better society . . . I guess it’s just that I glimpsed something beautiful in a flashbulb moment once, and perhaps mistaking it for a prophecy have been seeking its fulfillment ever since. And perhaps that nothing else in the world ever seemed to hold even this much promise. It may look like I make too much of all this. We could leave all significance at the picture of Mick Jones just a hot guitarist in a white jumpsuit and a rock ’n’ roll kid on the road obviously having the time of his life and all political pretensions be damned, but still there is a mood around The Clash, call it “vibes” or whatever you want, that is positive in a way I’ve never sensed around almost any other band, and I’ve been around most of them. Something unpretentiously moral, and something both selfaffirming and life-affirming—as opposed, say, to the simple ruthless hedonism and avarice of so many superstars, or the grim tautlipped monomaniacal ambition of most of the pretenders to their thrones.

BUT ENOUGH of all that. The highlight of the first day’s bus ride occurred when I casually mentioned that I had a tape of the new Ramones album. The whole band pratically leaped at my throat: “Why didn’t you say so before? Shit, put it on right now!” So I did and in a moment they were bouncing all over the van to the strains of “Cretin Hop”. “Rocket To Russia” (Nick Kent fool) thereafter became the soundtrack to the rest of my leg of the tour. I am also glad to be able to tell everybody that The Clash are solid Muppets fans. (They even asked me I had connections to get them on the show.) Their fave rave is Kermit, a pretty conventional choice if y’ask me—I’m a Fozzie Bear man myself.

That night as we were walking into the hall for the gig in Cardiff, Paul said, “Hey Lester, I just figured out why you like Fozzie Bear—the two of you do look a lot alike!” And then he slaps me on the back.

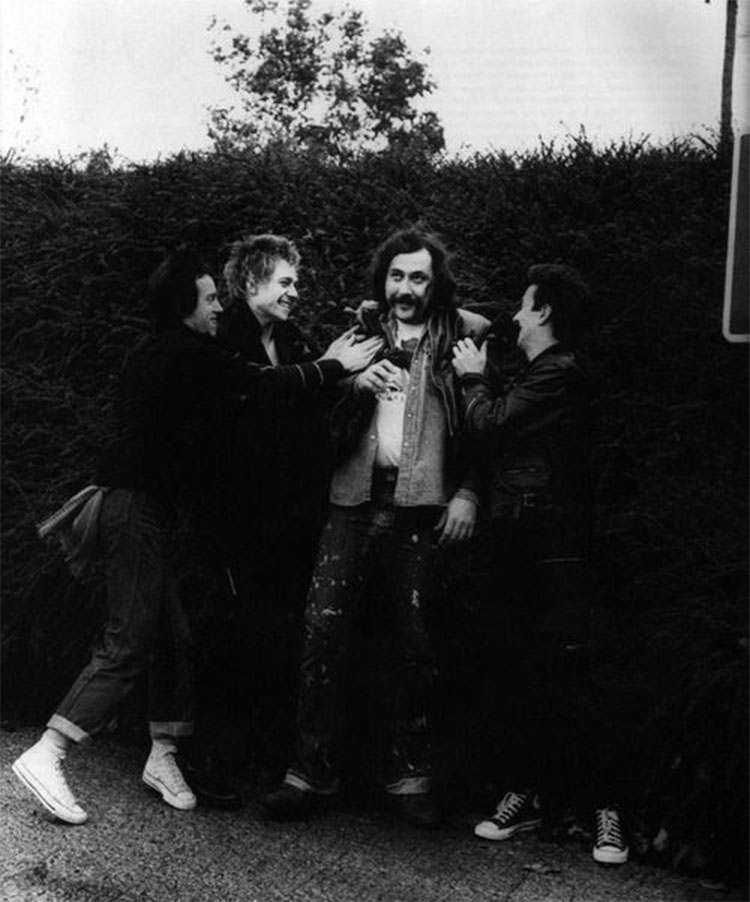

All right, at this point I would like to say a few words about this Simonon fellow. Namely that HE LOOKS LIKE A MUPPET. I’m not sure which one, some kinda composite, but don’t let that brooding visage in the photos fool you—this guy is a real clown. (Takes one to know one, after all.) He smokes a lot right, and when he gets really out there on it makes with cartoon non sequiturs that nobody else can fathom (often having to do with manager Bernie), but stoned or not when he’s talking to you and you’re looking in that face you’re staring right into a red-spiked bigeyed beaming cartoon, of whom it would probably not be amiss to say he lives for pranks. Onstage he’s different, bouncing in and out of crouch, rarely smiling but in fact brooding over his fretboard ever in ominous motion, he takes on a distinctly simian aspect; the missing link, cro-magnon, Piltdown man, Cardiff giant.

It is undoubtedly this combination of mischievous boychild and paleolithic primate which has sent swoonblips quavering through feminine hearts as disparate as Patti Smith and Caroline Coon—no doubt about it, Paul is the ladies’ man of the group without half trying, and I doubt if there are very many gigs where he doesn’t end up pogoing his pronger in some sweet honey’s hive. Watch out, though, Paul— remember, clap doth not a Muppet befit.

The gig in Cardiff presents quite a contrast to Derby. It’s at a college, and anybody who has ever served time in one of these dreary institutions of lower pedantry will know what manner of douse that portends. Once again the band delivers maybe 60% of what I know they’re capable of, but with an audience like this there’s no blaming them. I’m not saying that all college students are subhuman—I’m just saying that if you aim to spend a few years mastering the art of pomposity, these are places where you can be taught by undisputed experts.

Like here at Cardiff about five people are pogoing, all male, while the rest of the student bodies stand around looking at them with practiced expressions of aloof amusement plastered on their mugs. After it’s all over some cat goes back to interview Mick, and the most intelligent question he can think of is “What do you think of David Bowie?” Meanwhile I got acquainted with the lead singer of The Lous, a good all-woman band from Paris. She says that she resents being thought of as a “woman musician,” instead of a musician pure and simple, echoing a sentiment previously voiced to me by Talking Heads’ Tina Weymouth. “It’s a lot of bullshit,” she says. I agree; what I don’t say is that I am developing a definite carnal interest which I will be too shy to broach. I invite her back to our hotel; she says yes, then disappears. When we get there it’s the usual scene in the lobby, except that this time the management has thoughtfully set out sandwiches and beer. The beer goes down our gullets, and I’m just about to start putting the sandwiches to the same purpose when I discover somebody has other ideas: a clot of bread and egg salad goes whizzing to splat right in the hack of my head! I look around and confront solid wall of innocent faces. So I take a bite and wham! another one.

In a minute sandwiches are flying everywhere, everybody’s getting pelted, I’m wearing a slice of cabbage on my head and have just about accepted this level of chaos when I smell something burning. “Hey Lester,” somebody says, “you shouldn’t smoke so much!” I reach around to pat the back of my head and—some joker has set my hair on fire! I pivot in my seat and Paul is looking at me giggling. “Simonon you fuckhead—” I begin only to smell more smoke, look under my chair where there’s a piece of 8 × 10 paper curling up in flames. Cursing at the top of my lungs, I leap up and get a chair on the other side of the table where my back’s to no one and I can keep an eye on the red-domed Muppet. Only trouble is that I’ll find out a day or so hence that it wasn’t him set the fires at all: it was Bernie, the group’s manager. Eventually the beer runs out, and Mick says he’s hungry. Bernie refuses to let him take the van out hunting for open eateries, which we probably wouldn’t be able to find at 4 a.m. in Cardiff anyway, and we all go to bed wearing egg salad.

NEXT MORNING sees us driving to Bristol, a large industrial city where we put up in a Holiday Inn, much to everyone’s delight. By this time the mood around this band has combined with my tenacious jet-lag and liberal amounts of alcohol to put me into a kind of ecstasy state the like of which I have never known on the road before.

Past all the glory and the gigs themselves, touring in any form is a pretty drab and tiresome business, but with The Clash I feel that I have reapprehended that aforementioned glimpse of some Better World of infinite possibilities, and so, inspired and a little delirious, I forego my usual nap between vantrip and showtime by which I’d hoped to eventually whip the jet-lag, spending the afternoon drinking cognac and writing.

By now I’m ready to go with the flow, with anything, as it has begun to seem to me delusory or not that there is some state of grace overlaying this whole project, something right in the soul that makes all the headache-inducing day to day pain in the ass practical logistics run as smoothly as the tempers of the people involved, the whole enterprise sailing along in perfect harmony and such dazzling contrast to the brutal logistics of Led Zep type tours albeit on a much smaller level . . . somehow, whether it really is so or a simple basic healthiness on the part of all involved heightened by my mental state, I have begun to see this trip as somehow symbolic pilgrimage to that Promised Land that rock ’n’ roll has cynically sneered at since the collapse of the Sixties.

At this point, in my hotel room in Bristol, if six white horses and a chariot of gold had materialized in the hallway, I would have been no more surprised than at room service, would’ve just climbed right in and settled back for that long-promised ascent to endless astral weeks in the heavenly land. What I got instead around 6 p.m. was a call from Joe Strummer saying meet him in the lobby in five minutes if I wanted to go to the sound check. So I floated down the elevators and when I got there I saw a sheepish group of little not-quite punks all huddled around one couch. They were dressed in half-committal punk regalia, a safety pin here and there, a couple of little slogans chalked on their school blazers, their hair greased and twisted up into a cosmetic weekend approximation of spikes.

“Hey,” I said, ‘‘You guys Clash fans?” “Well,” they mumbled, “sorta . . .” “Well, whattaya mean? You’re punks, aren’t ya?” “Well, we’d like to be . . . but we’re scared . . .”

When Joe came down I took him aside and, indicating the poor little things, told him what they’d said, also asking if he wanted to get them into the gig with us and thus offer a little encouragement for them to take that next, last, crucial step out into full-fledged punk pariahdom and thus sorely-need-self-respect.

“Forget it,” he said. “If they haven’t got the courage to do it on their own, I’m bloody well not gonna lead ’em on by the hand.” On the way to the sound check I mentioned that I thought the band hadn’t been as good as I knew they could be the previous two nights, adding that I hadn’t wanted to say anything about it.

“Why not?” he said. I realised that I didn’t have an answer. I tell this story to point out something about The Clash, and Joe Strummer in particular, that both impressed and showed me up for the sometimes hypocritical “diplomat” I can be. I mean their simple, straightforward honesty, their undogmatic insistence on the truth and why worry about stepping on people’s toes because if we’re not straight with each other we’re never going to get anything accomplished anyway. It seems like such a simple thing, and I suppose it is, but it runs contrary to almost everything the music business runs on: the hype, the grease, the glad-handing. And it goes a long way towards creating that aforementioned mood of positive clarity and unpeachy morality. Strummer himself, at once the “leader” of the group (though he’d deny it) and the least voluble (though his sickness might have had a lot to do with it), conveys an immediate physical and personal impact of ground-level directness and honesty, a no-bullshit concern with cutting straight to the heart of the matter in a way that is not brusque or impatient but concise and distinctly nonfrivolous.

Serious without being solemn, quiet without being remote or haughty, Strummer offers a distinct contrast to Mick’s voluble wit and twinkle of eye, and Paul’s looney toon playfulness. He is almost certainly the group’s soul, and I wish I could say I had gotten to know him better.

From the instant we hit the hall for the sound-check we all sense that tonight’s gig is going to be a hot one. The place itself looks like an abandoned meatpacking room—large and empty with cold stone floors and stark white walls. It’s plain dire, and in one of the most common of rock ’n’ roll ironies the atmosphere is perfect and the acoustics great.

MEANWHILE BACK in the slaughterhouse, another thing occurs to me while The Clash are warming up at their soundcheck. They play something very funky which I later discover is a Booker T number, thus implanting an idea in my mind which later grows into a conviction: that in spite of the brilliance manifested in things like “White Riot”, they actually play better and certainly more interestingly when they slow down and get, well, funky. You can hear it in the live if not studio version of “Police and Thieves”, as well as “White Boy In Hammersmith Palais,” probably the best thing they’ve written yet.

Somewhere in their assimilation of reggae is the closest thing yet to the lost chord, the missing link between black music and white noise rock capable of making a bow to black forms without smearing on the blackface, get me! It’s there in Mick’s intro to “Police And Thieves” and unstatedly in the band’s whole onstage attitude. I understand why all these groups thought they had to play 120 miles per hour these last couple of years—to get us out of the bog created by everything that preceded them this decade—but the point has been made, and I for one could use a little funk, especially from somebody as good at it as The Clash.

Why should any great rock ’n’ roll band do what’s expected of ’em, anyhow? The Clash are a certain idea in many people’s minds, which is only all the more reason why they should break that idea and broach something else. Just one critic’s opinion y’understand but that’s what god put us here for.

In any case, tonight is the payload. The band is taut terror from the instant they hit the stage, pure energy, everything they’re supposed to be and more. I reflect for the first time that I have never seen a hand that moved like this: most of ’em you can see the rockinroll steps choreographed five minutes in advance, but The Clash hop around each other in all configurations totally non-selfconsciously, galvanised by their music alone, Jones and Simonon changing places at the whims of the whams coming out of their guitars, springs in the soles of their tennies.

Strummer, obviously driven to make up to this audience the loss of energy suffered by the last two nights’ crowds, is an angry live wire whipping around the middle of the front stage, divesting himself of guitar to fall on one knee in no Elvis parody but pure outside-of-self frenzy, snarling through his shattered dental bombsite with face screwed up in all the rage you’d ever need to convince you of The Clash’s authenticity, a desperation uncontrived, unstaged, a fury unleashed on the stage and writhing in upon itself in real pain that connects with the nerves of the audience like summer lightning, and at this time pogoing reveals itself as such a pitifully insufficient response to a man by all appearances trapped and screaming, and it’s not your class system, it’s not Britain-on-the-wane, it’s not even glandular fever, it’s the cage of life itself and all the anguish to break through which sometimes translates as flash or something equally petty but in any case is rock ’n’ roll’s burning marrow. It was one of those performances for which all the serviceable critical terms like “electrifying” are so pathetically inadequate, and after it was over I realized the futility of hitting Strummer for that interview I kept putting off on the “politics” of the situation.

The politics of rock ’n’ roll, in England or America or anywhere else, is that a whole lot of kids want to be fried out of their skins by the most scalding propulsion they can find, for a night they can pretend is the rest of their lives, and whether the next day they go back to work in shops or boredom on the dole or American TV doldrums in Mom ’n’ Daddy’s living room nothing can cancel the reality of that night in the revivifying flames when for once if only then in your life you were blasted outside of yourself and the monotony which defines most life anywhere at any time, when you felt supra-alive, when you supped on lightning and nothing else in the realms of the living or dead mattered at all.

Part Two: I Do Want a Baby Like That

(IN LAST week’s episode, our fearless though slightly misapprehensive Ishmael shipped out only to find the dreaded newpube Leviathan a massive—though not Trojan—lamb, which did not so much allay his quave as charm his pacifist heart. This week he continues on the White Star Liner to Coventry, a voyage fraught with anecdote and ruminations both utopian and pragmatic. So keep a close eye on him and a ratchet handy ’cause he could slip back into this penny-dreadful prose at a moment’s notice . . .)

BACK AT the hotel everybody decides to reconvene in the Holiday Inn’s bar to celebrate this back-in-form gig. I stop off by my room and while sitting on the john start reading an article in Newsweek called “Is America Turning Right?” (Ans: yes.) It’s so strange to be out here in the middle of a foreign land, reading about your own country and realising how at home you feel where you have come, how much your homeland is the foreign, alien realm.

This feeling weighed on me more and more heavily the longer I stayed in England—on previous visits I’d always been anxious to get back to the States, and New York homesickness has become a congenital disease whenever I travel. But I have felt for so long that there is something dead, rotten and cold in American culture, not just in the music but in the society at every level down to formularised stasis and entropy, and the supreme irony is that all I ever read in NME is how fucked up it is for you guys, when to me your desperation seems like health and my country’s pabulum complacency seems like death.

I mean, at least you got some stakes to play for. Our National Front has already won, insidiously invisible as a wall socket. The difference is that for you No Future means being thrown on the slagheap of economic refuse, for me it means an infinity of television mirrors that tell the most hideous lies lapped up by this nation of technocratic Trilbys. A little taste of death in every mass inoculation against the bacteria of doubt.

But then I peeked behind the shower curtain: Marisa Berenson was there. “I’ve got films of you shitting,” I said. “So what?” she said. “I just sold the negatives to WPLJ for their next TV ad. They’re gonna have it in neon laserium. I’ll be immortal.”

I mean, would you wanna be a ball bearing? That’s how all the television families out here feel and that’s how I feel when I go to discos, places where people cultivate their ballbearingness. In America, that is.

So what did I go down into now but the Bristol (remember Bristol?) Holiday Inn’s idea of a real swinging disco where vacationing Americanskis could feel right at home. I felt like climbing right up the walls, but there were girls there, and the band seemed amused and unafeared of venturing within the witches’ cauldron of disco ionisation which is genocide in my book buddy, but then us Americans do have a tendency to take things a bit far.

THIS CLUB reminded me of everything I was hosannah-glad to escape when I left New York: flashing dancefloors, ball bearing music at ballpeen volumes, lights aflash that it’s all whole bulb orgone bolloxed FUN FUN FUN blinker city kids till daddy takes the console away. I begin to evince overt hostility: grinding of teeth, hissing of breath, balling and banging of fists off fake naugahyde. Fat lot of good it’ll do ya, kid. Discotheques are concentration camps, like Pleasure Island in Walt Disney’s Pinocchio. You play that goddam Baccara record one more time, Dad, your nose is gonna grow and we’re gonna saw it off into toothpicks. I’m seething in barely suppressed rage when Glen Matlock, a puckish pup with more than a hint of wry in his eye, leans across the lucite teentall flashlight pina colada table and says, “Hey, wanna hear an advance tape of the Rich Kids album?”

“Sure!” You can see immediately why Glen got kicked out of the Pistols: I wouldn’t trust one of these cleanpop whiz kids with a hot lead pole. But I would tell ’em to say hello. I don’t give shit for The Raspberries and Glen looks an awful lot like Eric Carmen—except I can’t help gotta say it not such a sissy—and it’s all Paul McCartney’s fault anyway, and I mean McCartney ca. Beatles wonderwaxings we all waned and wuvved so well, but in spite of all gurgling bloody messes we’re just gonna have to keep on dealing with these emissaries from the land of Bide-a-Wee and His Imperial Pop the Magic Dragon, besides which I’d just danced to James Brown and needed some Coppertone oil and band-aids. Let’s see, how else can I insult this guy, shamepug rippin’ off the galvanic force of our PUNZ flotilla with his courtly gestures in the lateral of melody, harmonies, Hollies, all those lies? So he puts it on his tape deck and it’s the old Neil Diamond penned Monkees toon, “I’m a Believer”.

“Hey!” I said. “That’s fuckin’ good! That’s great! You gotta helluva band there! Better than the original!” Ol’ Puck he just keeps sitting back sipping his drink laughing at me through lighthouse teeth. Has this tad heard “Muskrat Love?”

“Whattaya laughin’ at?” I quack. “I’m serious. Glen, anybody that can cut the Monkees at their own riffs is okay in my book!” Then the next song comes on. It’s also a Monkees toon. “Hey, what is this—you gonna make your first album ‘The Monkees’ Greatest Hits’?” Well, I know I’m not the world’s fastest human . . . from the time it was released until about six months ago I thought Brian Wilson was singing “She’s giving me citations” (instead of the factual “excitations”) in “Good Vibrations”, I thought the song was about a policewoman he fell in love with or something. So as far as I’m concerned The Rich Kids SHOULD make their first album (call it this too, beats “Never Mind The Bollocks” by miles) “The Monkees Greatest Hits”. I’d buy it. Everybody’d buy it. Not only that, you could count on all the rock critics in NME to write lengthy analyses of the conceptual quagmire behind this whole helpful heaping scamful—I mean, let’s see Malcolm top that one. Come to think of it, the coolest thing the Pistols could have done when they finally got around to releasing their album would be to’ve called it “Eric Clapton”. Who cares how much it helps sales, think of the important part: the insult. Plus a nice surprise for subscribers to Guitar Player magazine, would be closet hearthside Holmstrummed Djangoes, etc. They don’t want a baby that looks like that, even if it’s last name is Gibson. Les Paul, where are you? Gone skateboarding, I guess.

With Dick Dale.

OH YEAH, The Clash. Well, closing time came along as it always has a habit of doing at obscenely punescent hours in England—I mean, what is this eleven o’clock shit anyway? Anarchy for me means the bars stay open 24 hours a day. Hmmm, guess that makes Vegas the model of Anarchic Society. Okay, Malcolm, Bernie, whoever else manages all those like snorkers and droners all over the place, it’s upROOTS lock stock and barrel time, drop the whole mess right in the middle of Caesar’s Palace, and since Johnny Rotten is obviously a hell of a lot smarter than Hunter S. Thompson we got ourselves a whole new American Dream here. No, guess it wouldn’t work, bands on the dole can’t afford past the slot machines, cancel that one. We go up to Mick’s room for beer and talk instead.

He’s elated and funny though somewhat subdued. I remark that I haven’t seen any groupies on this tour, and ask him if he ever hies any of the little local honeys up to bed and if so why not tonite?

Mick looks tireder, more wasted than he actually is (contrary to his git-pikkin hero, he eschews most all forms of drugs most all of the time) (whole damn healthy bunch, this—not a bent-spoon man or parlous freaksche in the lot). “We don’t get into all of that much. You saw those girls out there—most of ’em are too young.” (Quite true, more later.) “But groupies . . . I dunno, just never see that many I guess. I’ve got a girlfriend I get to see about once a month, but other than that . . .” he shrugs, “when you’re playin’ this much, you don’t need it so much. Sometimes I feel like I’m losin’ interest in sex entirely. “Don’t get me wrong. We’re a band of regular blokes. It’s just that a lot of that stuff you’re talking about doesn’t seem to . . . apply.”

See, didn’t I tell you it was the Heavenly Land? The Clash are not only not sexist, they are so healthy they don’t even have to tell you how unsexist they are; no sanctimony, no phonies, just ponies and miles and miles of green Welsh grass with balls bouncing . . . Now I will repeat myself from Part One that THIS is exactly and precisely what I mean by Clash = model for New Society: a society of normal people, by which I mean that we are surrounded by queers, and I am not talking about gay people. I’m talking about . . . well, when lambs draw breath in Albion with Sesame Street crayolas, we won’t see no lovers runnin’ each others’ bodies down, get me. I mean fuck this and fuck that, but make love when the tides are right and I do want a baby that looks like that. And so, secretly smiling across the rain, does William Blake.

NEXT DAY was a long drive South-West. Actually this being Sunday and my three days assignment up I’m sposed to go back to London, but previous eventide when I’d told Mick this he’d asked me to stick around and damned if I didn’t—a first for me. Usually you just wanna get home, get the story out and head beerward. But as y’all can see my feelings about The Clash had long ago gotten way beyond all the professional malarkey, we liked hanging out together. Besides which I still kept a spyglass out for that Promised Land’s colours seemed so sure to come a-blowin’ around every fresh hillock curve, hey there moocow say hello to James Joyce for me, gnarly carcasses of trees the day before had set to mind the voices “Under Milk Wood”. . . land rife with ghosts who don’t come croonin’ around no Post Houses way past midnite with Automatic Slim and Razor Totin’ Jim, no, the reality is you could be touring Atlantis and it’d still look like motorway :: car park :: gasstop :: pissbreak :: souvenir shop :: at deadening cetera. Joe kills the dull van hours with Nazitrocity thrillers by Sven Hassel, Mick is just about to start reading Kerouac’s The Subterraneans but borrows my copy of Charles Bukowski’s new book Love Is a Dog From Hell instead which flips him out so next two days he keeps passing it around the van trying to get the other guys to read certain poems like the one about the poet who came onstage to read and vomited in the grand piano instead (and woulda done it again too) but they seem unimpressed, Joe wrapped up in his stormtroopers and Paul spliffing in bigeyed space monkey glee playing the new Ramones over and over and everytime Joey shouts “LOBOTOMAAY!!” at the top of side two he pops a top out of somebody’s head, the pogo beginning to make like spirogyra, sprint- illatin’ all over the place, tho it’s true there’s no stoppin’ the cretins from hoppin’ once they start they’re like germs that jump. Meanwhile poor little Nicky Headon the drummer who I won’t get to know really well this trip is bundling jacket tighter in the front seat and swigging cough mixture in unsuccessful attempt to ward off miserable bronchold. At one point Mickey, the driver, a big thicknecked lug with a skinhead haircut, lets Nicky take the wheel and we go skittering all over the road.

Golly gee, you must get bored reading such stuff. Did you know that this toot is costing IPC (who, for all I know also put out a you’re-still-alive monthly newsletter for retired rear Admirals of the Guianean Fleet) seven and a half cents a word? An equitable deal, you might assert, until you consider than in this scheme of things, such diverse organisms as “salicylaceous” and “uh” receive equal recompense, talk about your class systems or lack of same. NOW you know why 99% of all publicly printed writers are hacks, because cliches pay good as pearls, although there is a certain unalloyed ineluctable Ramoneslike logic to the way these endless reams of copy just plow on thru and thru all these crappy music papers like one thickplug pencil’s line piledriving from here on out to Heaven. I mean look, face it, both reader and writer know that 99% of what’s gonna pass from the latter to the former is justa buncha jizjaz anyway, so why not just give up the ghost of pretence to form and subject and just make these rags ramble fit to the trolley you prob’ly read ’em on . . . y- on . . . y- may say that I take liberties, and you are right, but I will have done my good deed for the day if I can make you see that the whole point is YOU SHOULD BE TAKING LIBERTIES TOO. Nothing is inscribed so deep in the earth a little eyewash won’t uproot it, that’s the whole point of the so-called “new wave”—to REINVENT YOURSELF AND EVERYTHING AROUND YOU CONSTANTLY, especially since all of it is already the other thing anyway, The Clash a broadside a pamphlet an urgent handbill in a taut and moving fist, NME staff having advertised themselves a rock ’n’ roll band for so many years nobody can deny ’em now, as you are writing history that I read, as you are he as I am we as weasels all together, Jesus am I turning into Steve Hillage or Daevid Allen, over the falls in any case but at least we melted the walls leaving home plate clear for baseball in the snow.

ARE YOU an imbecile? If so, apply today for free gardening stamp books at the tubestop of your choice. Think of the promising career that may be passing you by at this very moment as a Greyhound. Nobody loves a poorhouse Nazi. Dogs are more alert than most clerks. Plan 9: in America there is such a crying need for computer operators they actually put ads on commercial TV begging people to sign up.

British youth are massively unemployed. Relocate the entire under-25 population of Britain to training centres in New Jersey and Massachusetts. Teach them all to tap out codes. Give them lots of speed and let them play with their computers night and day. Then put them on TV smiling with pinball eyes: “Hi! I used to be a lazy sod! But then I discovered COMPUTROCIDE DYNAMICS INC., and it’s changed my life completely! I’m happy! I’m useful! I walk, talk, dress and act normal! I’m an up and coming go getter in a happening industry! Good Christ, Mabel, I’ve got a job.” He begins to bawl maudlinly, drooling and dribbling sentimental mucous out his nose. “And to think . . . that only two months ago I was stuck back in England . . . unemployed, unemployable, no prospects, no respect, a worthless hunk of human shit! Thank you, Uncle Same!”

So don’t go tellin’ me you’re bored with the U.S.A., buddy. I’ve heard all that shit one too many pinko punko times. We’ll just drink us these two more beers and then go find a bar where you know everybody is drinkin’ beer they bought with money they owned by the sweat of their brow, from workin’, get me, buddy? ’Cause I got a right to work. Niggers got a right to work, too. Same as white men. When your nose is pushin’ up grindstone you got no time to worry about the size of the other guy’s snout. Because you know, like I know, like we know, like both the Vienna Boys’ Choir and the guy who sells hot watches at Sixth Avenue and 14th St. know, that we were born for one purpose and one purpose only: TO WORK. Haul that slag! Hog that slod! Whelp that mute and look at us: at our uncontestible NOBILITY: at our national biological PRIDE: at our stolid steroid HOPE.

Who says it’s a big old complicated world? I’ll tell ya what it comes down to, buddy: one word: JOB. You got one, you’re okay, scot-free, a prince in fact in your own hard-won domain! You don’t got one, you’re a miserable slug and a drag on this great nation’s economically rusting drainpipes. You might just as well go drown yourself in mud. We need the water to conserve for honest upright workin’ folks! Folks with the godsod sense to treat that job like GOLD. Cause that’s just what it stands for and WHY ELSE DO YOU THINK I KEEP TELLING YOU IT’S THE MOST IMPORTANT THING IN THE UNIVERSE? Your ticket to human citizenship.

One man, one job. One dog, one stool.

THE HOTEL has a lobby and coffeeshop which look out upon a body of water which no one can figure out whether it’s the English Channel or not. Even the waitresses don’t know. I’m feeling good, having slept in the afternoon, and there’s a sense in the air that everybody’s up for the gig.

Last night consolidated energies; tonight should be the payload. We wind through narrow streets to a small club that reminds me much of the slightly sleazy little clubs where bands like the Iron Butterfly and Strawberry Alarm Clock, uh, got their chops together, or, uh, paid whatever dues were expected of them when they were coming up and I was in school. This type of place you can write the script before you get off the bus; manager a fat middle-aged brute who glowers over waitresses and rockbands equally, hates the music, hates the kids but figures there’s money to be made. The decor inside is ersatz-tropicana, suggesting that this place has not so long ago been put to uses far removed from punk rock. Enrico Cadillac vibes.

I walk in the dressing room which actually is not a dressing room but a miniscule space partitioned off where three bands are supposed to set up, almost literally on top of one another. The Voidoids’ Bob Quine walks in, takes a look and lays his guitar case on the floor; “Guess this is it”.

Neither of the opening acts have been getting the audience response they deserved on this tour. These are Clash audiences, people who know all their songs by heart, have never heard of The Lous and maybe are vaguely familiar with Richard Hell. Richard is totally depressed because his band isn’t getting the support he hoped for from their record company on this trek. The “Blank Generation” album hasn’t been released yet—The Voidoids think it’s because Sire wants to flog a few more import copies, although I hear later in the week that strikes have shut down all the record pressing plants in Britain. The result is that the kids in the audience don’t know most of the songs, the lyrics, nothing but that Ork/ Stiff EP to go on, so they settle for gobbing on the band, screaming for The Clash.

I tell Hell and Quine that I have never heard the band so tight, which is true—there’s just no way that night-after-night playing, in no matter how degraded circumstances, can’t put more gristle and fire in your playing. Interestingly enough, Ivan Julian and Marc Bell, Hell’s second guitarist and drummer, are both in good spirits—they’ve toured before, know what to expect—while Hell and Quine are both totally down.

Someday Quine will be recognised for the pivotal figure that he is on his instrument—he is the first guitarist to take the breakthroughs of early Lou Reed and James Williamson and work through them to a whole new, individual vocabulary, driven into odd places by obsessive attention to “On the Corner” era Miles Davis. Of course I’m prejudiced, because he played on my record as well, but he is one of the few guitarists I know who can handle the supertechnology that is threatening to swallow players and instrument whole—“You gotta hear this new box I got,” is how he’ll usually preface his latest discovery, “it creates the most offensive noise . . .”—without losing contact with his musical emotions in the process. Onstage he projects the cool remote stance learned from his jazz mentors—shades, beard, expressionless face, bald head, old sportcoat— but his solos always burn, the more so because there is always something constricted in them, pent-up, waiting to be let out.

Tonight’s crowd is good—they respond instinctively to The Voidoids though they’re unfamiliar with them, and it doesn’t seem at all odd to see kids pogoing to Quine’s Miles Davis riffs. (He steals from Agharta! And makes it work!) Hell and the Voidoids get the only encore on my leg of the tour, and they make good use of it, bringing Glen Matlock out to play bass. The Clash’s set is brisk, hot, clean—consensus among us fellow travellers is that it’s solid but lacks the cutting vengeance of last night.

Even on a small stage—and this one is tiny—the group are in constant motion, snapping in and out of one anothers’ territory with electrified sprints and lunges that have their own grace, nobody knocking knees or bumping shoulders, even as The Voidoids in certain states which they hate and I think among their best reel and spin in hair’s- breadth near-collisions with each other that are totally graceless but supremely driven. You can really see why Tom Verlaine wanted Hell out of Television—he flings himself all over the stage as if battering furiously at the gates of some bolted haven, and if Ivan and Bob know when to dodge you can also see plainly why Hell would have been in a group called The Heartbreakers—because that sumbitch is hard as oak, and he’s just looking for the proper axe because something inside seethes poisonously to be let out.

I would also like to say that Richard Hell is one of the very few rockers I’ve ever known who I could slag off in print and still be friends with. After my feature on him in this magazine I was half-wondering if I was gonna have another Patti Smith (cracked and bitter “I am the Oracle!”) on my hands, but he was totally cool if contentious about it—a sane person, in other words.

BACK IN the dressing room I met some fans. There was Martin, who was 14 and had a band of his own called Crissus. I thought Martin was a girl until I heard his name (no offence, Martin) but look at it this way: here, on some remote southern shore of the old Isle, this kid who is just entering puberty, this child has been so inspired by the New Wave that he is already starting to make his move. I asked him whether Crissus had recorded yet, and he laughed: “Are you kidding?”

“Why not? Everybody else is”. (Not said cynically either.) I asked Martin what he liked about The Clash in particular as opposed to other New Wave bands. His reply: “Their total physical and psychic resistance to the fascist imperialist enemies of the people at all levels, and their understanding of the distinction between art and propaganda. They know that the propaganda has to be palatable to the People if they’re going to be able to a) be able to listen to it b) understand it, and c) react to it, rising in Peoples’ War. They recognise that the form must be as revolutionary as the content—in Cuba they did it with radio and ice cream and baseball and boxing, with the understanding that sports and music are the most effective vectors for communist ideology. Rock ’n’ roll as a form is anarchistic, but if we could just figure out some way to make the content as compelling as the form then we’d be getting somewhere! “For the present, we must recognise that there is only so much revolutionary information that can be transmitted in so circumscribed a space and time, after all, and so we must be content in the knowledge that the potency of form ensures the efficacy of content, that is that the driving primitive African beat and boarlike guitars will keep bringing the audience back for repeated hypnotised listenings until the revolutionary message laid out plainly in the lyrics cannot help but sink in!”

Martin was bright for his age. Not quite as bright as all that, though. Or maybe brighter. Because of course he didn’t say that. I made that up. What Martin said was, “I like The Clash because of their clothes!”

And so it went with all the other fans I interviewed over the six nights I saw them. Nobody mentioned politics, not even the dole, and I certainly wasn’t going to start giving them cues. This night, I got such typical responses as: “Their sound—I dunno, it just makes you jump!” “The music, which is exciting, and the lyrics, which are heavy, and the way they look onstage!” (which is stripped down to zippers and denims for instant combat, or perhaps stage flexibility).

As we were all wandering out, Mick in the middle of a cluster of fans as usual, not soaking up adoration but genuinely interested in getting to know them, about halfway between bandstand and door, the owner of the club began making noises about “Bleedin’ punk rockers—try to have a decent club, they come in here and mess it up—”

Mick looked at him indifferently. “Bollocks.”

“Look, you lot, clear out, now, we don’t want your kind hanging round here,” and of course he has his little oaf-militia to hustle them toward the exits. Finally I said to him, “If you dislike them so much, why don’t you open a different kind of club?”

Instantly he was up against me, belly and breath and menace: “Wot’re you lookin’ for some trouble, then?”

“No, I just asked you a question.”

You know, it’s like all the other similar scenes you’ve ever seen all your life—YOU REALLY DON’T WANT TO GET INTO SOME KIND OF STUPID VIOLENCE WITH THESE PEOPLE, but you finally just get tired of being herded like swine.

WHEN WE got out front a few Teds showed up—first I’d seen in England, really, and I had the impulse to go gladhanding up to them every inch the Yankee tourist gawker dodo: “Hey, you’re Teds, aren’t you? I’ve heard about you guys! You don’t like anything after Gene Vincent! Man, you guys are one bunch of stubborn motherfuckers!” I didn’t do that, though—I looked at Mick and the fans, and they looked wary, staring at indistinct spots like you do when you scent violence in the air and don’t want it. They were treading lightly. But then, outside of certain scenes with each other, almost all the punks I’ve ever seen tread lightly! They’re worse than hippies! More like beatniks.

But what was really funny was that the Teds were treading lightly too—they just sort of shuffled up with their dates, in their ruffled shirts and velour jackets and ducktail haircuts, shoved their hands in their pockets and started muttering generalities: “Bleedin’ punks . . . spunks . . . shit . . . bun bloody freaks . . .” Really, you had to strain to hear them. They seemed almost embarrassed. It was like they had to do it. I had never seen anything quite like it in the U.S., because aside from certain ethnic urban gangs, there is nothing in the U.S. quite like the Teds-Punks thing. We’ve got bikers, but even bikers claim contemporaneity. The Teds seemed as sad as the punks seemed touching and oddly inspiring—these people know that time has passed them by, and they are not entirely wrong when they assert that it’s time’s defect and not their own. They remember one fine moment in their lives when everything—music, sex, dreams—seemed to coalesce, when they could tell everybody trying to strap them to the ironing board to get fucked and know in their bones that they were right. But that moment passed, and they got immensely scared, just like kids in the U.S. are mostly scared of

New Wave, just like people I know who freak out when I put on Miles Davis records and beg me to take them off because there is something in them so emotionally huge and threatening that it’s plain “depressing.”

The Teds were poignant for me, even more so because their style of dress made them as absurd to us as we were to them (but in a different way—they look “quaint,” a very final dismissal). They looked like people who had had one glimpse in their lives and were supping at the dry bone of that memory forever, but man, that glimpse, just try to take it away from me, punk motherfucker . . . not that the punks are trying to infringe on the Teds—just that unlike the punks, who pay socially for their stance but at least have the arrogance of their freshness, the Teds looked like people backed into a final corner by a society which simply can’t accept anybody getting loose.

In America you can ease into middle age with the accoutrements of adolescence still prominent and suffer relatively minor embarrassment: okey, so the guy’s still got his sideburns and rod and beer and beergut and wife and three kids and a duplex and never grew up. So what? You’re not supposed to grow up in America anyway. You’re supposed to consume. But in Britain it seems there is some ideal, no, some dry river one is expected to ford, so you can enter that sedate bubble where you raise a family, contribute in your small way to your society and keep your mouth shut. Until you get old, that is, when you can become an “eccentric”—do and say outrageous things, naughty things, because it’s expected of you, you’ve crossed to the other mirror downslide of the telescope of childhood.

In between, it looks like quiet desperation all the way to an outsider. All that stiff-upper-lip, carry-on shit. If Freud was right when he said that all societies are based on repression, then England must be the apex of Western Civilisation. There was a recently published conversation between Tennessee Williams and William Burroughs, in which Burroughs said he didn’t like the English because their social graces had evolved to a point where they could be entertaining all evening for the rest of their

lives but nobody ever told you anything personal, anything real about themselves. I think he’s right. We’ve got the opposite problem in America right now—in New York City today there’s a TV talk show host who’s so narcissistic that every Wednesday he lays down on a couch and pours out his insecurities to his analyst . . . on the air!

You guys strike me as a whole lot of people who laugh at the wrong time, who constantly study the art of concealment. Then again, it occurs to me that it could actually be that there is something irritating me that you don’t suffer from—which is certainly not meant as selfaggrandizement on my part—but that you’ve been around a while, have come to wry terms with your indigenous diseases, whereas we Americans got bugs under our skin that make us all twitch in Nervous Norvusisms that must amuse you highly. But even here there is a difference— at our best we recognise our sickness, and stuggle constantly to deal with it. You’re real big on sweeping the dirt under the carpet. So it’s no wonder that, like Johnny Rotten says, you’ve got “problems”—more like boils bursting, I’d say.

AND NOW, as I get ready to close off, I feel uncomfortably pompous and smug—I’ll be back with the payoff next week, the sum of what I see in this whole “punk” movement, for anybody who want to hear it—but here I sit on what feels like a sweeping and enormously presumptuous generalisation on not just the punks but your whole country.

Well, then, let the fool make a fool out of himself, but I’ll tell you one thing: the Teds are a hell of a symptom of the rot in your society, much more telling in their way than the punks, because the punks, much as they go on about boredom and no future, at least offer possibilities, whereas the Teds are landlocked. You cocksuckers have effectively enclosed these people, who are only trying to not give up some of their original passions in the interests of total homogenization, in an invisible concentration camp. Your contempt stymies them, so they strike out at the only people who are more vulnerable and passive than they are: the punks.

The almost saintly thing about the punks is that for the most part they don’t seem to find it necessary to strike out with that sort of viciousness against anybody—except themselves. So to anyone who is reading this who is in a position of “status,” “responsibility,” “power,” unlike the average NME reader, I say congratulations—you’ve created a society of cannibals and suicides.

Legal, fui direto ler mas em inglês!!!!